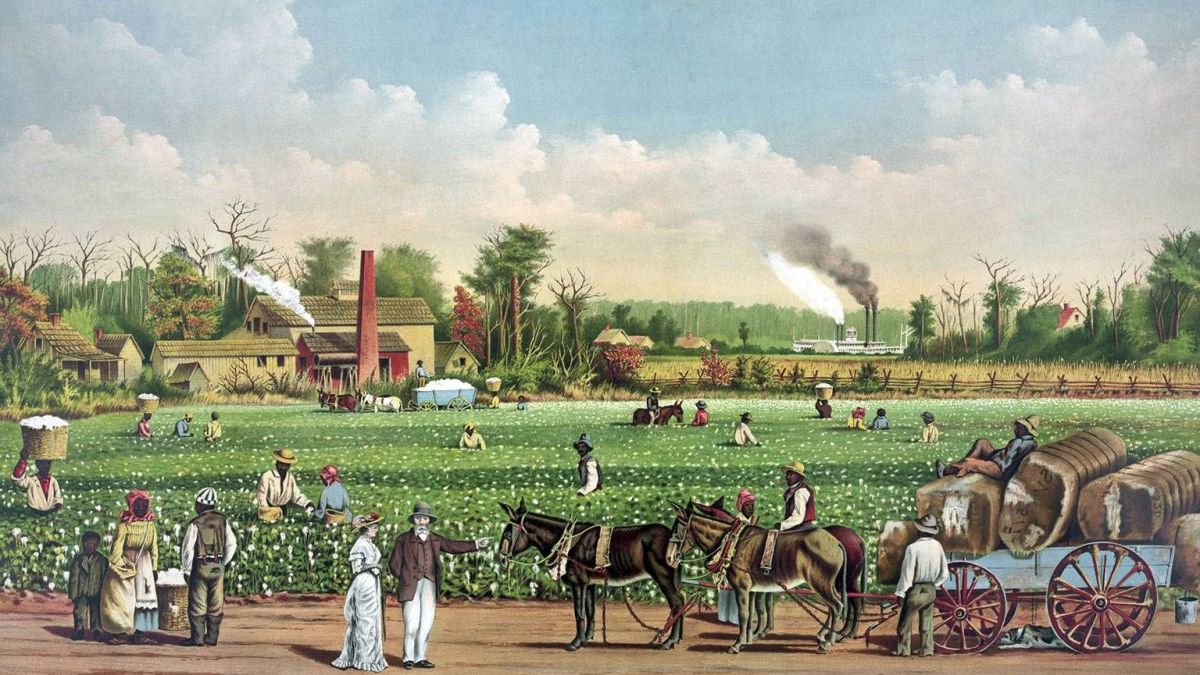

In the early 1500s, having struck it rich with the Incas and Aztecs, the Spanish began to probe Florida and Southeastern North America for more gold. In these excursions, they learned much about the geography of the New World and its indigenous people but uncovered little material wealth. The Amerindians proved to be farmers and hunter gatherers, not empire builders. Florida and the Southeast never became more than a backwater region for Spain and was important mostly as a strategic buffer between New Spain, its Caribbean colonies, and the burgeoning English colonies to the north.

Ponce de Leon was the first European to land on Florida in 1513, and he charted the Atlantic coast down to the Florida Keys and north along the Gulf Coast. In 1521, he sailed from Cuba with 200 men in two ships to establish a colony on the southwest coast of the Florida peninsula, but vicious attacks from the local Calusa forced the colonists to flee. In one of the skirmishes, Ponce de León was wounded in his thigh and later died from the wound.

In 1525 Lucas Vázquez de Ayllón set out with six ships carrying 700 colonists to establish a settlement at Sapelo Sound, Georgia, which he called San Miguel de Gualdape. They landed too late to plant crops and were not able to get help from the local Mississippians. After only three months and the death of Ayllón, the remaining 150 survivors abandoned the colony and fled back to Spain.

Next came Panfilo de Narváez who tried to settle the Gulf Coast of Florida in 1527. After landing and setting out for the interior to find food and gold, the local people attacked them and they were forced to retreat back to the coast, where they built boats and sailed westward and then traveled on foot across Texas and Northern Mexico to New Spain. De Narvaez died on route and only four members of his party made it back alive, after wandering through the Southwestern US and northern Mexico for eight years.

Hernando de Soto led an invasion force for four years and four months (1539 – 1543) marching through Florida, South Carolina, North Carolina, and Tennessee, before heading southwest through the northwestern corner of Georgia into central Alabama and down the Mississippi River. They traveled from one indigenous community to another following local trails and camping near villages where stores of maize could be found. They discovered many rich agricultural societies but little gold and silver.

Pedro Menéndez de Aviles was sent by King Philip II in 1565 to explore the coast of Florida, disrupt any French settlements he found, and build a permanent outpost. He and his solders established the first permanent city of European origin in North America at St. Augustine and cleared the area of French intruders. He then tried to seal Spain’s hold on the Southeast by founding a series of forts and settlements at every deep water port across the region. This expansion proved ephemeral as subsequent famines, mutinies, and Indian warfare gradually whittled the Spanish presence back to Saint Augustine.

A group of Jesuits who had accompanied Aviles to Florida opened several missions along the southeastern coast and in the interior of Florida, but these efforts ultimately failed in 1572 due to hostilities with the local Amerindians. Franciscans came the following year to resume the effort and built several missions, but they too faced considerable rebellion and native intransigence, and had only limited success.

Illustration: 17th century Spanish engraving (colored) of Juan Ponce de León. Wikipedia

Bibliography:

Hoffman, P. E. (1990) A New Andalucia and a Way to the Orient: The American Southeast during the Sixteenth Century. Louisiana State University Press, Baton Rouge

Hudson, C. (1997) Knights of Spain, Warriors of the Sun: Hernando de Soto and the South’s Ancient Chiefdoms. Athens, University of Georgia Press.

Lockhart, J. and Stuart B. Schwartz, S. B. (1983) Early Latin America: A History of Colonial Spanish America and Brazil. Cambridge University Press

For more histories of agriculture and trade: https://www.worldhistory.org/user/geneticsofberries