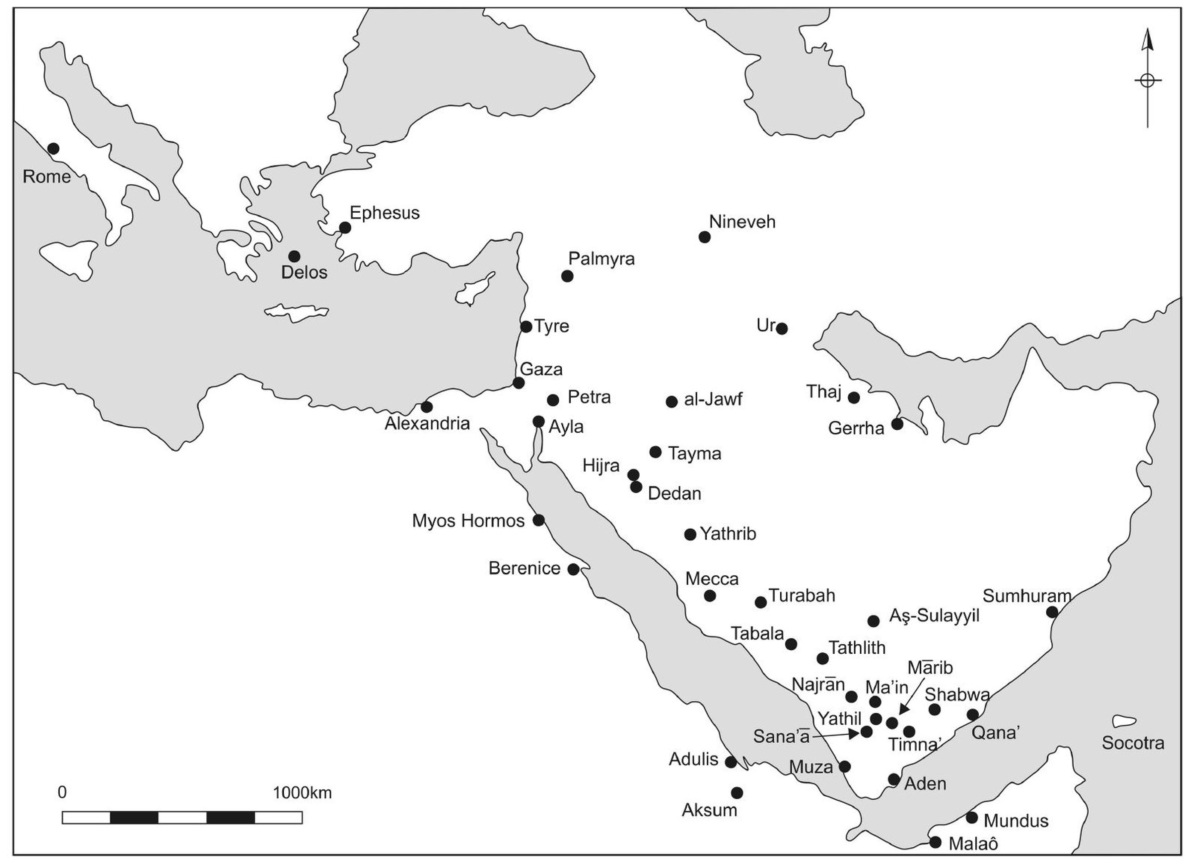

A great trade route evolved across Arabia to serve the insatiable desire for incense in Egypt and the other ancient societies of Mesopotamia. What came to be called the “Incense Route” wove from southern Arabia along the Red Sea coast and west through the Sinai to trade frankincense and myrrh. These Incense Routes flourished most mightily between the 7th century BCE and the 2nd century CE, but had roots that went back as far as 1200 BCE.

Great caravans of camels carried frankincense and myrrh from Yemen to the Mediterranean, weaving their way across vast stretches of largely inhospitable terrane. The traders had to travel around towering mountains, find water and shelter in desert infernos and fend off bands of thieves. There was essentially only one trail in southern Arabia that met these necessities.

The caravan leaders were well versed in the overland routes, knowing every oasis, well, shelter, settlement and taxation point. By 500 BCE, the caravans were huge, encompassing 200 camels or more. These large convoys provided mutual security against roaming bandits and protection against the harsh, unforgiving desert. A fully loaded camel could predictably travel at a rate of 2.5 miles an hour, so the caravan leaders could decide where and when the caravan would rest each day.

From Shabwa, the caravans journeyed southwest through the desert to the capital of the Qatabanian Kingdom, Timna. Here exotic goods from India, Sri Lanka and Southeast Asia could be added to their cargo for transport north. These goods were brought here from the South Arabian ports, principally Aden. The Greeks referred to Aden as Arabia Emporion, or Arabia’s emporium.

From Timna, the caravans headed northwest to Ma’rib, about 90 miles away in the Kingdom of the Sabians. It could be reached directly through a desert with towering, dry sand dunes, but most merchants probably took the longer route through the mountains between the two cities. The Qatabanian’s had gone to great pains to build special passes through the most difficult points which allowed travelers to pass single file on leveled surfaces. Of course, there were numerous religious shrines and Qatabanian tax collectors along the way.

In Ma’rib, the travelers passed by a massive dam which has been called by many as the engineering marvel of the age. The Ma’rib dam was twice as long as the Hoover Dam built in the Black Canyon of the Colorado River in the 1930s. It must have been a great relief for the travelers to have come to the green oasis surrounding the great Ma’rib dam and it is likely that the travelers lingered there for a few days, purchasing supplies and resting. Next facing them was the Sayhad desert, of which there was no way around. The Roman’s called it Arabia Deserta, (desert Arabia) in comparison to Arabia Felix (happy Arabia) from where they came. They dove deep into the desert until finally arriving at the oasis of Najrn. Here the trail bifurcated with one route heading northeast to the port city of Gerrha on the Persian Gulf, and the other heading direct north to Yathrib,

Gerrha was a thriving metropolis of middlemen who bought aromatics and spices from the South Arabians and sold them goods from all over the known world including multicolored textiles and embroideries from Phoenicia, Persia and Anatolia. Yathrib served not only the caravans but also pilgrims headed to the holy city of Mecca, a few days away. Yathrib achieved fame as the place the Prophet Mohammed sought sanctuary in 622 AD after fleeing persecution in Mecca.

From Yathrib, the merchants had the choice of heading northeast to Mesopotamia (Babylonia or Assyria) along the edge of the great Nafud Desert, or north-west to the Mediterranean. Those merchants heading to the Mediterranean would have continued trudging seven more days to Dedan, the capital of the Lihyanite kingdom, where a thriving colony of Minaean merchants lived 2,000 years ago.

Merchants heading north to the Levant and Anatolia would have then travelled through Petra, the capital city of the Nabataean Kingdom. Petra served as an important hub of trade, linking the Red Sea ports of Egypt with southern Arabia, East Africa and the coast of India. It also came to serve as a terminus of the Silk Road reaching all the way to northeastern China..

The last stop on the northern route was Gaza, the main spice trading center of the ancient Graeco-Roman world . This city sat on the southern edge of the Mediterranean, midway between Jerusalem and Alexandria and was the terminus of all the overland trade routes carrying not only incense, but also spices and silk. From Gaza, the trade goods were shipped to Alexandria, which became the most important processing centre for goods destined for the Greek and Roman Empires.

At journey’s end, the incense from southern Arabia had traveled a prodigious distance. Pliny the Elder estimated the distance between Timna, at the start of the incense trail and Gaza, at the northern terminus, was 2,437,500 steps or about 1500 miles. The journey would have taken about 65 days by camel. The incense that found its way to Puteoli through Gaza on its way to Rome traveled another 1,500 miles by sea for a total journey of about 3,000 miles.

Adapted from: Hancock, J. (2021) Chapter 5. Spices, scents and silk: Catalysts of trade. CABI, Wallingford, UK

Picture: Cities along the Incense Route.